Sunday, November 20, 2005

Fondo Alberto Moravia

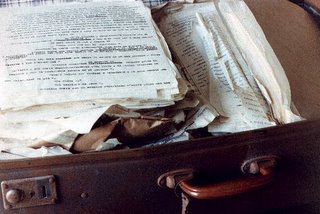

The Fondo Alberto Moravia was founded in 1991 by the sisters, the heirs and some friends of the writer and is located in Rome in the house where he lived. The Fondo owns the writer's manuscripts and archives, a consulting library and catalogue of articles and publications, and photographic and audio-visual documents on the writer. It organises cultural activities to honour the memory of Moravia in different fields (literature, criticism, theatre, cinema, 'civil engagement') and participates to national and international events.

Since 1993, awards are assigned every year to an university thesis (from national and foreign universities) and to a film script inspired by the work and/or life of the writer, to children's drawings inspired by Moravia's tales Storie della Preistoria, and to italian and foreign writers. Since 1997, it issues a semestrial review, Quaderni. The Fondo has produced some short documentary films and has published Moravia al/nel Cinema. The library and archives of the Fondo Alberto Moravia, and the house, can be visited by appointment at Associazione Fondo Alberto Moravia. Lungotevere della Vittoria n.1, 00195 Roma info: 06.3203698 - fondoalbertomoravia@virgilio.it

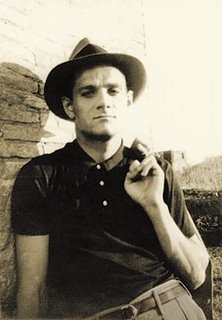

The photograph of Moravia at the beginning of this Blog is reproduced from http://www.pinosettanni.it/Gallery1/01%20alberto%20moravia%201987.jpg

Alberto Moravia (1907-1990) - pseudonym of Alberto Pincherle

Italian journalist, short-story writer, and novelist. Moravia explored in his books sex, social alienation and other contemporary issues - he was the major figure in the 20th-century Italian literature. Moravia was married to Else Morante (1941-1963), who also was a writer, best known for her novel LA STORIA (History, 1974). Several of Moravia's books have been filmed, among them Two Women by Vittorio De Sica (1960), A Ghost at Noon by Jean-Luc Godard (1964), and The Conformist by Bernardo Bertolucci (1970).

Alberto Pincherle (Alberto Moravia) was born in Rome into a well-to-do middle-class family. His mother was Teresa (de Marcanich) Pincherle, and father, Carlo Pincherle, an architect and a painter. At the age of nine, Moravia was stricken with tubercular infection of the leg bones, which he considered the most important factor in his early development. He spent considerable periods from 1916 to 1925 in sanatoria. He walked with the aid of a walking stick throughout his later life.

During these years Moravia started to write, and published at his own expense his first major novel, GLI INDIFFERENTI (Time of Indifference) in 1929. It is regarded as the first European Existentialist novel. The story focuses on three days in the life of a Roman family, who keep up a bourgeois front while living at the edge of poverty. The condemnation of the Roman bourgeoisie under fascism became a sensation. Not to arouse the disapproval of the authorities, Moravia wrote in an allegorical style, but his increasing involvement in politics led to his books being banned.

Later Moravia in his other books used the typical characters of an impotent intellectual, his virile rival, a voluptuous seductress, and an aging mistress. Generally Moravia women are strong. He saw sex as the enemy of love. Variations on the women of Gli indifferenti are found in LA ROMANA (1947, The Woman of Rome), in which the protagonist, Adriana, is a prostitute, and LA CIOCIARA (1958, Two Women). Moravia's criticism of society is presented on an allegorical level - proletariat is raped by capitalism, Italy loses her innocence under Fascism.

In the 1930s Moravia worked as a foreign correspondent for La Stampa and La Gazetta del Popolo. He travelled extensively abroad. His works were censored by Mussolini's fascist government, and placed by the Vatican on the Index librorum prohibitarum (Index of Forbidden Books). Moravia sharply criticized the dehumanized, capitalist world. After the publication of LE AMBIZIONI SBAGLIATE (1935, The Wheel of Fortune), Moravia lost his job at the Gazetta del Popolo.

In 1937 Moravia's collection of short stories L'IMBROGLIO appeared, which included L'Architetto, La Tempesta, and La Provinciale. Several of his stories were first published in newspapers. RACCONTI ROMANI (1954, Roman Tales) and NUOVI RACCONTI ROMANI (1959, More Roman Tales) include some of Moravia's best sketches of working-class characters in everyday situations.

From 1941 to 1943 Moravia lived in Anacapri (Capri). In 1943 he tried to escape to Naples, but unable to cross the frontier, fled with his wife Elsa Morante into the mountains of Ciociaria. He had written in 1941 a comic parody of the Mussolini government, LA MASCHERATA (The Fancy Dress Party), attacked fascism in his articles in Il Popolo di Roma, and was in danger of being arrested. He went into hiding in the peasant community in Fondi, near Cassino, until the Allied Liberation.

In 1944 he started to write Two Women, but returned to the work ten years later, when he had gained more distance from his own experiences. However, the nine months among peasants strengthened his social conscience and new sympathy for the people, which was evident in the short novel AGOSTINO (1944). In IL CONFORMISTA (1951) Moravia portrays a person, Marcello, who has dedicated himself to total conformity.

In the 1950s Moravia abandoned the third-person narrative, and used the limited, non-objective first person narrative in tune with the modernist literature theories. IL DISPREZZO (1954, A Ghost at Noon) was the basis of Jean-Luc Godard's film Le Mépris (1963).

In 1953, Moravia co-edited Nuovi Argomenti; he wrote film reviews from 1955 for L'Espresso. Between the years 1958 and 1970 he travelled throughout the world, and produced such travel books as The Red Book and the Great Wall (1986) and Which Tribe Do You Belong To? (1974). In 1982 he edited Nuovi Argomenti with Leonardo Sciascia and Enzo Siciliano. Among Moravias later works are LA NOIA (1960, The Empty Canvas), an examination of the relationship between reality and art, L'ATTENZIONE (1965, The Lie), about a novelist writing a work entitled L'attenzione, and IO E LUI (1971, The Two of Us), a story of a screenwriter who tries to understand his independently behaving penis, which constantly leads him into humiliating situations. LA VITA INTERIORE (1978, Time of Desecration) was composed in the form of an interview between the ostensible narrator and the interviewee, Desideria.

He wrote for several magazines, contributing to Corriere della Sera regularly from 1946. From his wide travels in different places of the world Moravia produced several articles and travel books, including UN MESE IN URSS (1958), LA RIVOLUZIONE CULTURALE IN CINA (1968), and VIAGGI. ARTICOLI 1930-1990 (1994). Moravia's autobiography appeared in 1990. His philosophical and political scepticism did not prevent him from entering politics. In 1984 he was elected Italian representative to the European Parliament. Moravia died in Rome on September 26, 1990. He lived most of his life in Rome; the city played an important role in his fiction.

Moravia and Rome are one.

This summary of Moravia's life and career is derived from: http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/moravia.htm

Saturday, November 19, 2005

Alberto Moravia

by

Tina Kaszinski

Alberto Moravia was an Italian novelist, short story writer, playwright, poet, and essayist. Moravia became ill as a child with tuberculosis so he was deprived of a formal education. He studied at home throughout his childhood and became very good at reading and writing. He was at home with this illness until he was twenty-five years old so studying was about the only activity possible. It was during this time that Moravia began to respect books.

By the time he was twenty-two years old he took the literary world by storm with The Time of Indifference, which criticized fascism and the social situation that began the flourishment. "This is a novel that is a realistic picture of middle-class corruption that flaunted the ruling fascist government's policy of idealistic formalism in art; the novel depicts sex as a basic psychological need and the most significant human activity.(Ross and Freed, 1972)

Moravia is one of the best known Italian writers outside of his country. His early works deserve great respect, but during the early 1970s his work started having a falling out of quality. He uses his sense of humor to express his two main themes: he is a critic of `bad faith' and explores the strains on males by their loneliness that lets them escape by exploiting women.

In his writings, the world, is presented as being corrupt (in which humans are guided by their senses,) and sex is valued over love. He is a specialist in sex but he feels sex is a means of power. The goal of sex is not pleasure, or reproduction; it is dominance over others.(Heiney, 1968) We all have problems of communication and this is true all over the world so people can relate to his writings. All of his writings include the theme of finding oneself due to having some kind of contact with the opposite sex. Some people believe that Moravia is a `sex freak' and I somewhat agree. Moravia's males have always been more satisfactory creations than the females. Moravia has females in his stories seem shallow, unbelievable, and most of the time sexually promiscuous.

Moravia has always been on the left side of the government, and has been criticized for it. During the war he spent most of the time on the run because his writings criticized fascism. He did not like Mussolini so he depicted a comical portrait of him, which made Mussolini's police clerks harass him. Moravia was warned that the Gestapo was planning his arrest because of certain antifascist articles he had written after the fall of Mussolini in July 1943, so he packed up and headed south. He spent nine months with the peasants and shepherds with led to a new outlook in his writings on lower class people.( Rebay, 1970,) Living with peasants, he developed a great interest in them and a sincere sympathy for their problems. He wrote four novels out of this era about this lower class.(Cottrell, 1974)

As an antifascist during Mussolini's regime, he was almost close to being labeled an enemy of the state.

During the 1940s his writings were directed towards Marxism. It was during this time that he had fled from Rome to live with the peasants in rural Italy. In 1941, he was forbidden to publish at all or even to write for newspapers but he still wrote under the pseudonym "Pseudo."(Heiney, 1968) In the 1950s Moravia's focus left Marxism and settled on intellectual solutions to world problems. In the more recent years, Moravia's concerns have been "the dehumanizing effects of society and technology, the human psyche, and the breakdown of communication." During Mussolini's regime he wrote a novel, 1934, which concentrated on the obsessive qualities of politics, money, and sex. In fascist society Moravia depicts that love, friendship, trust, and honesty cannot exist; only self-interests exist.(Cottrell, 1974) Everyone must be a trickster to survive and Moravia was against this.

Some critics have judged him as an author who covers the same ground over and over again. They feel that he is not very inventive or stylish, but most critics believe Moravia is trying to express his concerns to the full potential.

Moravia's view of life is tragic because he fears that man has become a machine. He states, "the use of man as a means, and not as an end, is the root of all evil." He believes in survival out of life's circumstances and suffering. He uses crime and brutality over and over in his writing. Fascism was very hard on Italians, and Mussolini thought war was ideal, so he organized it. Moravia is an antifascist and was against violence. He had many concerns about fascism and stressed them in his writings.

Compassion is the key to life, not only for yourself but for others. Moravia wants us to accept the challenge of assuming the sorrows of others, and to suffer because of others. People should work together, as the antifascist groups did in opposing Mussolini.

As an antifascist in the 1930s and 1940s during Benito Mussolini's regime, Moravia was subject to careful scrutiny. It was during this time "Moravia depicted characters who abused others as a means of self-satisfaction...which could be construed by censors as allusions to fascist politics."(Heiney, 1968) The rise of fascism took off after WWI when the territorial gains were less than promised. Italy was promised territory in the Alps but the war was a disaster and 600,000 lives were lost. Many people looked down on the government and were conditioned to adopt fascism.

Italy was prepared for Mussolini to rise to power because of high unemployment and inflation due to the war. Fascism replaced an ineffective and insufficient government. Mussolini was a very strong leader but had to have complete control. This is one reason Moravia was harassed by Mussolini for speaking out against fascism. He was losing power if he would allow an antifascist to diminish Mussolini's character.

During this fascist period, Mussolini produced unemployed, bitter people. Anyone hoping for a job had to be a fascist so Moravia turned to writing. In 1926, Mussolini moved people who spoke against him to islands, so Moravia was lucky he was only harassed instead of banned from the state. Government officials were appointed because he wanted fascists to take these spots. It was quite impossible to live in Italy as an antifascist during this time. When Moravia wrote, he had to be very careful of what he said because Italy did not have free speech. It is a law that you cannot speak against the dictator. It was either be a fascist and live a normal life or be an antifascist and live a life of silence.

In 1939, Mussolini joined alliance with Germany under Hitler. The Nazis flooded into Italy and these events caused his popularity to drop dramatically. Moravia was born a Jew but was baptized as a Catholic so he was even more against fascism since Mussolini sided with the Nazis. It was a great accomplishment for the antifascists because after Mussolini's dismissal in 1943, Italy voted for a democratic government with antifascist ideas. Italians felt betrayed and wanted nothing to do with fascism.

Moravia was influential during the fascist period and after it. Many influential writers hailed him as a "creative genius," but Mussolini's brother Arnaldo stated in a public speech that he was opposed to having young Italians read an author such as Moravia, "a destroyer of every human value." The fascists hated his books which painted such an unflattering picture of Italian society and youth, even if they spoke the truth. Both before and after the war he worked frequently in the cinema, and several of his novels ere made into films.(Heiney, 1968)

On January 1, 1948 a new Italian Constitution was written and finished. This is an antifascist constitution which determines civil liberties which were taken away by fascism. It wasn't until this time that antifascists actually had a chance to express their ideas in Italy. In 1941, Moravia even had a novel confiscated by Fascist authorities. There is no democracy in that situation and it is ridiculous that Mussolini had that much power by himself.

Moravia believed that the ultimate political sin was egotism or failure to comprehend or take into account the political needs of others; it is this characteristic that made fascism possible. In almost all of his novels Moravia is in disguise, such as in Il Conformista he is a fascist spy.(Heiney, 1968)

Moravia saw Italy as a deteriorating country under fascism. He expressed this view through the more than 30 books he published in his lifetime. He was one of the best Italian novelists throughout his life, and he is well respected to this day. Alberto Moravia died in 1990 of a cerebral hemorrhage and his final novel was published in 1991. He remained faithful to himself over his forty-odd years of writing. He followed personal lines of development, reaching the goals he set for himself. Moravia used the same themes again and again but for the purpose of getting his message across effectively. He would have liked to change his theme, but his fiction reflects the world he lived in. Moravia hopes for a change in the world and believes we can achieve this by exposing the problems through his writing.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bergin, T. G. (1953, Spring). The Moravian Muse. The Virginia Quarterly Review, 215-25.

Cottrell, J. E. (1974). Alberto Moravia. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co.

Freed, D., Ross, J. (1972). Contemporary Literary Criticism. (Vol. 27, p. 353-355). Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press.

Heiney, D. (1968). Three Italian Novelists. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

Peterson, T. E. (1996). Alberto Moravia. New York: Twayne Publishers.

Rebay, L. (1970). Alberto Moravia. Columbia University Press. Seymour-Smith, M. (1976). Who's Who in Twentieth Century Literature. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Revised 5/20/97